A tale of 2–make that 1 and 1/3–screens

Wednesday | March 18, 2009 open printable version

open printable version

DB here:

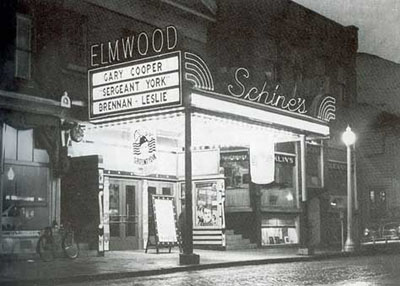

Last week family affairs took me back to my home area, the Finger Lakes region of New York State. About ten miles from our farm lies the village of Penn Yan (short for Pennsylvania Yankees). When I was growing up there in the 1950s and 1960s, Penn Yan boasted about 3500 people—enough to support one movie theatre. That theatre, the Elmwood on Elm Street, was where I saw most of the movies I didn’t see on TV.

The Elmwood was my introduction to film. When my parents went to town, I was embedded with hundreds of other kids in Saturday afternoon matinees of Tarzan and Lone Ranger movies. On Friday nights, I might catch June Allyson, Donald O’Connor, or Martin and Lewis. When I got older I saw Lawrence of Arabia and From Russia with Love. The Elmwood showed a fair number of art films in the 1960s, including The Servant, The L-Shaped Room, and even 8 ½ (dubbed, I think).

Built in the early 1920s, the Elmwood was acquired by the Schine brothers in 1936. Some towns in our area had two or three Schine theatres. Schine Amusements penetrated Auburn, Bath, Canandaigua, Corning, Cortland, Glens Falls, Gloversville (where it all started), Hamilton, Herkimer, Lockport, Massena, Oneonta, Oswego, Perry, Rochester, Salamanca, Seneca Falls, Syracuse (four houses), Tupper, and Watertown. Clearly, they were leaving the major cities to the big boys. The firm also owned venues in Kentucky and Ohio (none in Cleveland or Cincinnati, but three in Bucyrus). By snapping up screens in the sticks, Meyer and Louie Schine wound up holding nearly a hundred screens in their prime.

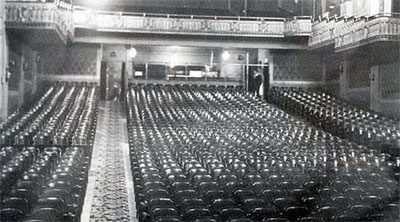

Although the brothers went for the smaller markets, they didn’t forget the amenities. They contracted some of the top theatre architects, notably John Eberson, a fantasist with eclectic tastes. The Elmwood didn’t benefit much from the Schines’ largesse as far as I can tell, but it was a sturdy place, with 838 seats, or one for every four people in town.

The Elmwood passed out of the Schines’ hands and eventually closed in the early 1970s. For awhile it was an indoor tennis court. The village offices now sit on the site. (Photo: Darlene Bordwell.)

But Penn Yan still has three screens, which I discovered when my sister Diane Verma and I went to Ken Kwapis’ He’s Just Not That Into You. It’s a network narrative like Kwapis’ earlier Sexual Life, and like that (and his Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants) it has some affecting and clever moments. There’s also a nice handling of shot/ reverse-shot when characters are turned away from each other. Mainly, though, I went to see the town’s multiplex, the Lake Street Plaza Theatres.

Converted from an exercise club, the LSP houses three screens in a bare-bones design typical of many multiplexes.

A young man, whose father owned the complex, sold the tickets and ran the projectors. A young woman handled the concession stand. Both were friendly and talkative. Diane and I, two of four people in the house, left happy, although the sugar in the Dots may have helped raise our mood.

Earlier that day, Diane, my other sister Darlene, and I were driving around our childhood haunts. The towns here are hollowed out by the big-box stores and the recession. Mall parking lots are full, but the main streets are desolate and many storefronts are empty.

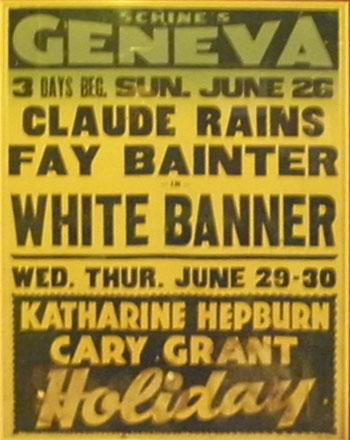

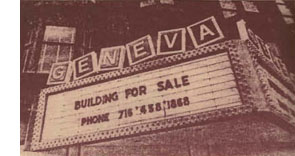

Yet in another lake town we came across a surprise. At first I was puzzled. How could the Geneva Theatre have been replaced by a much older and more dignified building, the Smith Opera House?

The door was ajar.

Inside Bruce Purdy, the Technical Director and professional magician, and Sharon Barnes were preparing for a children’s play. They kindly led us on an exploration of this half-hidden jewel. It may have assumed its old name, but the building has regained the delirious splendor that was the Geneva in its heyday.

The Smith Opera House was built in 1894. To its stage came Sousa, Bill Bojangles Robinson, Ellen Terry, and traveling shows mounted by Belasco. The vaudeville programs started including short films during the 1910s, and the Smith was one of thirteen venues in which Edison screened his experiments in talking pictures. The Birth of a Nation played there. Soon the theatre became a movie house, called initially the Strand. It wasn’t the only film theatre in town, and by the late 1920s it had competition. The nearby Regent had already become a picture palace, with about 1000 seats; it screened its first sound picture, John Ford’s Four Sons, in 1928 (presumably in a music-plus-effects version).

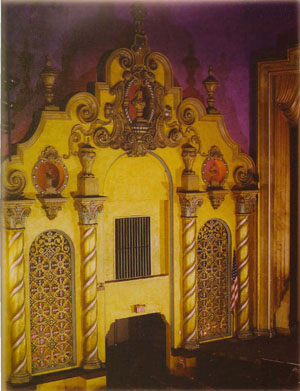

Enter, on cue, the Schines. They bought the Smith, and after playing burlesque there for some months, they decided to revamp it as a picture palace. The process took several years. The interior was stripped; opera seats were sold for a dollar each. What emerged was an “atmospheric,” with the dome displaying shifting clouds that would slowly clear to reveal twinkling stars. The architecture was a fanciful mix of Art Deco, Baroque, Art Nouveau, and Moorish influence. The premise was that you were in a courtyard under the heavens, surrounded by facades of buildings that were implausible but vaguely familiar in their exoticism.

With over 1800 seats, the Geneva Movie Theatre was advertised as the largest movie house in central New York. The first film to play there was Keaton’s Parlor, Bedroom, and Bath in March 1931. The manager, Mr. Gerald Fowler, stayed in charge until 1965.

I didn’t go to the Geneva as often as the Elmwood. Not until I got my Learner’s Permit (a life-changing event to country youth) was I able to drive to Geneva on my own. At the Geneva I saw Mary Poppins, What’s New, Pussycat?, and the CinemaScope version of How the West Was Won. I have no memories of the décor, but by all accounts it was decaying.

Like the Elmwood, the Geneva was closed in the 1970s. Today it looks spanking new. It hosts musical acts (Ani DeFranco is coming up), local and touring stage productions, and on weekends films, “mostly foreign and arthouse,” as Bruce Purdy explained. When we were there the theatre was running a package of Academy Award Best-Picture nominees.

My sisters and I first paused in the lobby, with its fine hanging lamps.

Inside, the auditorium area is of course very impressive, flanked by facades with corkscrew columns.

Along the balcony are vaguely ziggurat wall designs.

Just in case there was too much empty space, architect Victor Rigamount added some escutcheons.

In the projection booth, Bruce showed us the Brenkograph, a marvelous old gadget for projecting lantern slides in dissolving views. The Brenkograph provided the milky clouds cast onto the ceiling: light was pumped through a swirling oil mixture.

In 1946, the year before I was born, US movie attendance reached its peak of about 82 million weekly. The industry had receipts of nearly $1.6 billion. It must have looked like filmgoing would never fall off. But it did, and fast. Enjoying Peter Pan, Moby Dick, and Davy Crockett, I was living through the first major decline in the film industry. By the time I left for college in 1965, weekly US attendance had dropped to 20 million, where it would hover for nearly three decades. Hollywood’s annual box-office receipts were then $927 million (about $657 million in 1947 dollars). In the course of my eighteen years the country had lost 5,000 screens and about 50,000 theatre jobs.

I wish I could go back to see how these old theatres looked then. I wish I could photograph them, inside and out. I wish that I could return to the Elmwood in June 1954 to ask Mr. Norman Williams (unmarried) about the new screen, said to be twenty feet high and 35 feet long—redesigned, of course, for CinemaScope. He was planning to add stereophonic sound, which would, the newspaper story explains, “create the illusion that the sound travels with the movement of actors or objects across the screen.” But until the new system arrived, Mr. Williams said, only Warner Bros’ CinemaScope pictures would be run, because they didn’t require stereo. You mean movies like A Star Is Born and Rebel without a Cause? What wouldn’t I give to see those in their original form, from the front row.

I wish I could go back to see how these old theatres looked then. I wish I could photograph them, inside and out. I wish that I could return to the Elmwood in June 1954 to ask Mr. Norman Williams (unmarried) about the new screen, said to be twenty feet high and 35 feet long—redesigned, of course, for CinemaScope. He was planning to add stereophonic sound, which would, the newspaper story explains, “create the illusion that the sound travels with the movement of actors or objects across the screen.” But until the new system arrived, Mr. Williams said, only Warner Bros’ CinemaScope pictures would be run, because they didn’t require stereo. You mean movies like A Star Is Born and Rebel without a Cause? What wouldn’t I give to see those in their original form, from the front row.

Just before I left the area in 1965, I could have quizzed the managers and staff about the old days. After the war, had they suspected what was coming? What was it like to watch your livelihood shrivel year by year? I didn’t know enough to ask. I didn’t understand what had happened.

In the meantime, we haven’t lost everything. On one screen of the Lake Shore Plaza, you could have seen Watchmen on opening weekend. The projection is very good.

My general information about theatres and attendance is culled from back volumes of The Film Daily Yearbook. The Schine family entered history in another way; see here. Information about CinemaScope at the Elmwood comes from the Penn Yan Chronicle-Express of 10 June 1954, p. 1. My account of the Geneva Theatre is largely derived from two publications, The Smith Opera House (Geneva: n.d.) and Charles McNally’s The Revels in Hand: The First Century of the Smith Opera House, October 1894-October 1994 (Geneva: Finger Lakes Regional Arts Council, 1995). Both are available at the theatre; for contact information go here. The Elmwood photos come from wetlandspy. Check out Darlene’s photo page too.

For a panoramic study of American movie exhibition, see Douglas Gomery’s Shared Pleasures: A History of Movie Presentation in the United States. The first time I met Doug, he asked where I was from. I said Penn Yan. He nodded. “Okay, so you went to a Schine theatre.” The man knows his stuff.

Thanks to Bruce Purdy and Sharon Barnes for their hospitality. And thanks to Ryan Kelly for asking me to clarify the situation with Four Sons.